Peer review is wonderful, in theory. Scientists reviewing other scientists’ work to evaluate whether the science was applied thoroughly, implemented well, and interpreted effectively can be a wonderful way to allow the best science through. But the Reproducibility Project clearly demonstrated that something is broken – when over a quarter of the published studies reviewed could not be replicated.

It is not a surprise to most. Humans are involved. We make mistakes. We have our own biases, as was so well described recently by Philip Ball in a piece in Nautilus.

So I begin this post with the assumption that the current system is not perfect. And neither is what I am going to suggest… Is it not time to explore different methods, methods that take advantage of today’s world of rapid communication and self-publication?

Is the current process for peer review no longer consistent with the scientific method itself? If not, then why did it take such an effort to make a point that a lot of the science done is not as straightforward?

data-animation-override>

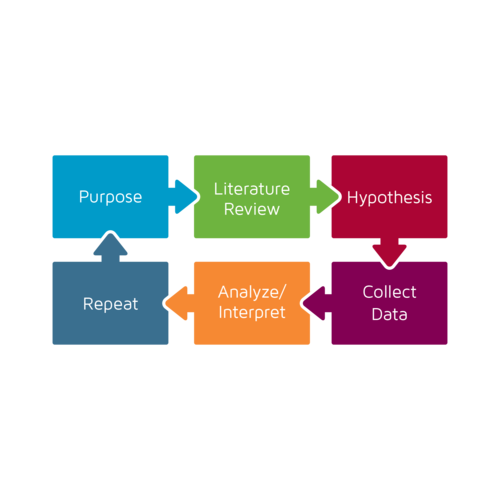

“The scientific method is a cycle. When we turn that cycle, we learn. When we learn, the science moves forward.”

The scientific method is a cycle. When we turn that cycle, we learn. When we learn, the science moves forward. The faster we can facilitate the process, the greater our advancements will be.

How does the current peer review process fit into this method? The peer review process limits available literature, it does not effectively provide a platform for hypotheses declaration, and it makes access to data sometimes more difficult. It often reduces space available for variations in analysis and interpretation due to length restrictions and editing. It limits others’ ability to replicate.

Traditional Scientific Method in the Social Sciences.

The technical infrastructure is there with platforms such as the Open Science Framework and the Dataverse Project, and blogging/publication platforms such as WordPress.com, Tumblr, Blogger, and Squarespace (the platform for this blog). Some have even written about using blogs to communicate your science: 9 Reasons Why Running A Science Blog Is Good For You.

I don’t suggest that we drop the traditional peer review process – it certainly has its place for seminal career defining research that has already survived the test of critique over time through incremental steps. But for those incremental pieces themselves, those smaller building blocks that eventually lead to the “big one”, is there not a better way?

Why don’t we start putting those findings out there on our own, with full transparency so that they can be reproduced or refuted? Leave the door open for others to replicate (and declare their successes or failures to do so right alongside). Allow for feedback and critiques. Let your research stand the test of time (or pass as we collectively learn new things).

Let’s consider the dissemination of results as part of the scientific method itself – not an end by which we simply measure our prestige.