Text messages (also known as Short Message Service, or SMS) have become the go-to medium when contacting others. This is especially the case for today’s college students, who seem to conduct their social and even business lives completely via messaging service.

SoundRocket examined the data surrounding the efficacy of using SMS when surveying college students, resulting in presentation at a past American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) Conference.

THE QUESTION

As college students move toward SMS as a primary means of communication, we wondered if SMS could be a feasible mode to contact students regarding surveys, and thus increase survey response? More specifically, could surveys using SMS more closely integrate survey participation into students’ daily routines?

THE CHALLENGES OF USING SMS

Using SMS has its challenges – both in implementation and quality. Challenges include:

- Ensuring students provide proper consent for the research team to contact them by SMS.

- Adapting to SMS message length in order to receive the highest possible rate of response.

- Navigating IRB and human ethics board requirement.

THE RESEARCH AND PRESENTATION WAS A COLLABORATION::

- Scott D. Crawford, SoundRocket, Ann Arbor, MI

- Sara O’Brien, SoundRocket, Ann Arbor, MI

- Colleen A. McClain, University of Michigan Institute of Social Research, Ann Arbor, MI

- Toben F. Nelson, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, MN

ARTICLE ABSTRACT

In a baseline survey of undergraduate and graduate students at a large midwestern University, over 60 percent reported they owned a smartphone (this was 2012; that percentage is undoubtedly much higher now). Slightly more than 45 percent said they used their smartphones every day to check email.

In this baseline survey, we informed students that we would be conducting “follow up studies in the near future” and would “like to have the option of contacting you via text/SMS message.”

Almost 20 percent agreed to participate in the upcoming study and told us they would provide us with their mobile phone number and nearly 98 percent of those actually did so. Those who did were younger and more likely to be female undergraduate students. Those who consented also reported higher levels of technology use.

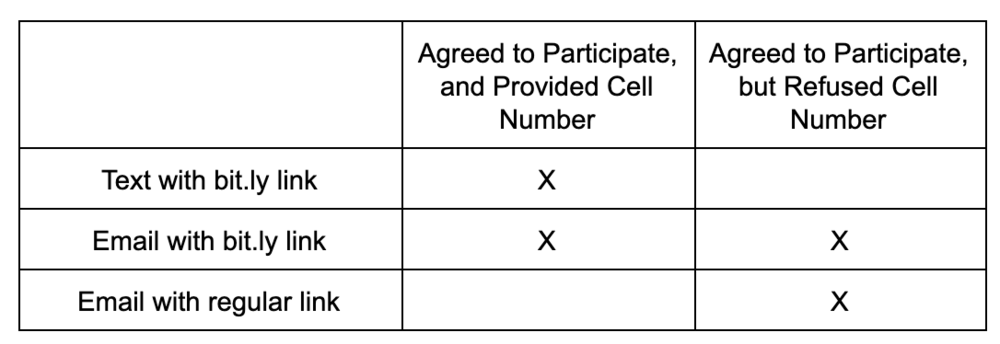

We randomly assigned each student who consented into one of two groups: those who received the survey via text and those who received it via email with a short bit.ly link.

Among those who consented to participate in the follow-up survey, but who didn’t approve of SMS use, we also randomly assigned them into one of two groups: one group received very short emails with a bit.ly (shortened) url and the second received emails with regular-length urls.

While none of the text messages we sent failed, we did find it difficult to craft a message that kept within the standard SMS message length – and remain relevant and clear.

The majority of responses came in via smart phone – with fewer than 10% completing via a mobile tablet. Often differences in completion rates are found between those who respond via mobile devices vs. those who respond on a computer – but in this study we found no such difference. Completion rates on both device types hovered around 95%.

WRAPPING UP

Surveying students via SMS/text has its challenges: it’s not an optimal mode of contact. However, we find that it may have value when used to supplement protocols for the right type of data collection and with the right respondents.

There is still more to discover about this research. To continue learning about the feasibility of SMS survey communication, fill out this form to receive a copy of the presentation on this study given at the AAPOR conference.